I was recently invited to speak at a medical conference in Athens on “innovation in ancient Greek medicine”, and I subsequently wrote a piece about the topic here.

Scholars consider the ancient Greek requirement that medical science rely on empirical observation to be one of the most important of medical innovations in history. Ironically, Greek physicians themselves, far from calling their empirical practice innovative, claimed it was age-old tradition. Rather, new ideas were to be shunned: “Medicine needs no new principle!”, we read in an ancient medical treatise. The phrase reminds me of a favourite film from the 1990s, Strictly Ballroom, in which the dancing competition adjudicator thunders that ‘there are no new steps!”

The surviving ‘Hippocratic Corpus’ contains around 60 treatises by different hands composed during the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Several Hippocratic books called Epidemics present case studies focussing on symptoms, environment, and patient histories. Notably, these case studies often end with the patient’s death, reflecting a commitment to the truth even in cases of failure. Referring to the way patients under the care of physicians will often die even while the ‘art’ (technê) of medicine continues to progress by means of careful observation of health and disease, Hippocrates is quoted as having said

“Life is short, art long, opportunity fleeting, experimentation perilous, and judgment difficult”.

ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή, ὁ δὲ καιρὸς ὀξύς, ἡ δὲ πεῖρα σφαλερή, ἡ δὲ κρίσις χαλεπή.

This is abbreviated into the Latin maxim Ars longa, vita brevis, a pithy statement that reminds us that while life is short, the things human beings create—art, music, scientific discoveries, and so on—can live on to inspire future generations.

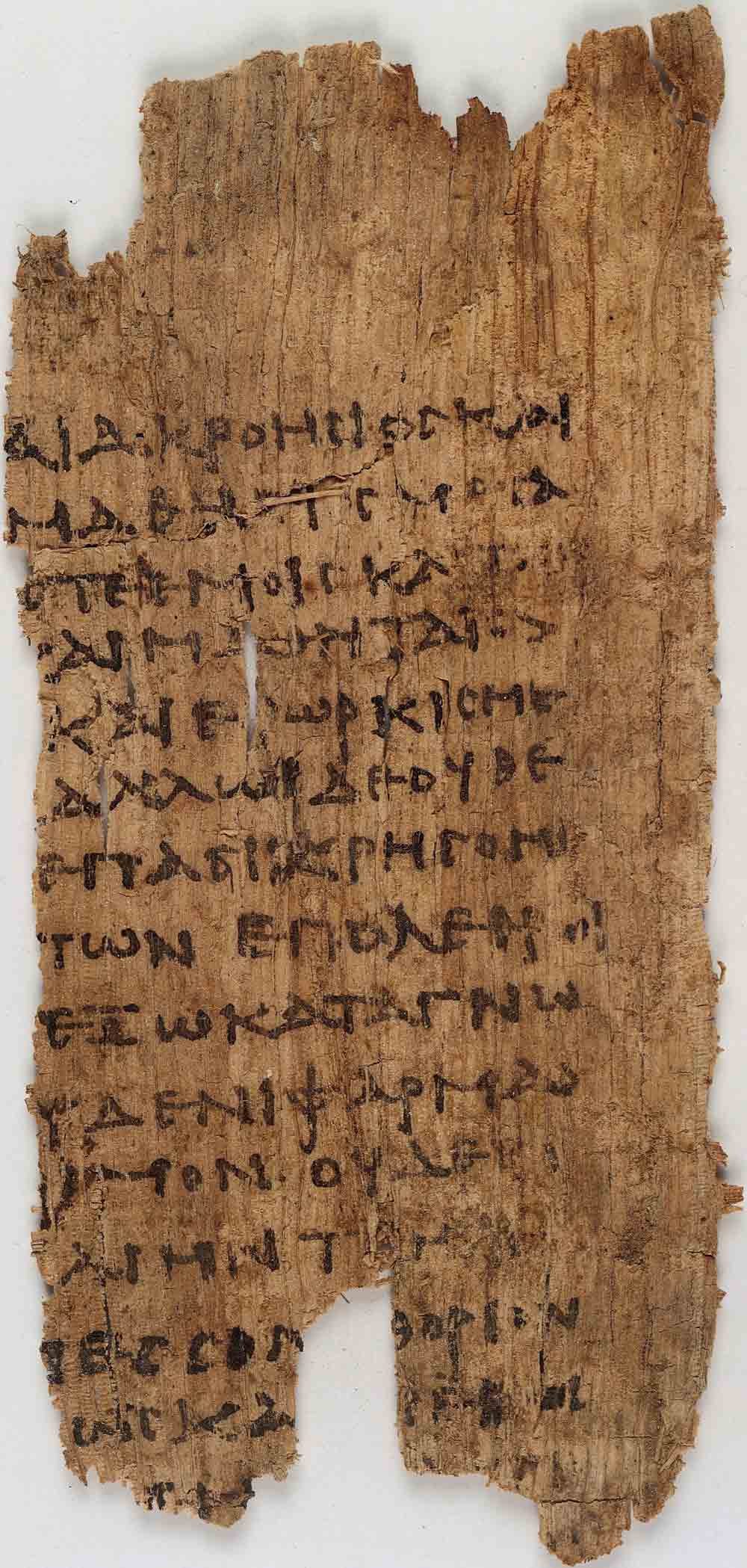

Hippocratic medicine became known for “humoral theory” - the idea that health is a balance of four bodily fluids (roughly corresponding to hot, cold, wet, and dry): blood, bile, black bile, and phlegm. An excess of any of these was said to make a person too “sanguine”, “choleric”, “phlegmatic” or “melancholic”. This unscientific doctrine, rooted in Greek notions of harmony and balance, dominated medicine until the advent of modern science. However, the Hippocratic Oath (shown on the papyrus fragment above) outlines a commitment to ethical standards and medical professionalism, and remains relevant in its requirement that doctors respect the autonomy, dignity, and confidentiality of their patients.

The humoral theory reminded me of the Ayurvedic concept of Doshas. The three doshas are vata, kapha, and pitta, each a combination of aakash (space), jala (water), prithvi (earth), teja (fire), and vayu (air) elements.

How interesting to see this fragment again and to try and unravel it. Thank you very much for your stimulating remarks and recording.

It would be good to see ἡ τέχνη translated as skill (or similar) rather than the Latin derived ‘art’ - especially as the Greeks were such a pragmatic bunch.