Where I teach as a classics tutor at Jesus College, Oxford University, we have an unusual method for teaching the Latin and Greek languages. For the past six years we have taught the ancient languages to undergraduates by having expert tutors who speak to them in Latin and (for two years) in ancient Greek as well, and by requiring the students to communicate orally in the languages. It is called active language learning.

Some students will already have studied the languages for a few years at school, others will be starting more or less from scratch. But we find that they mostly begin on a level playing-field when it comes to learning to speak the languages, which requires a different kind of effort from composing prose in writing. Speaking gives them the habit of summoning quickly to mind the right words and phrases, and we have found that in most cases translating Latin and Greek texts – and translating into Latin and Greek – feels far less forbidding as a result than it does to students taught with traditional methods. (NB we also ensure that grammar is taught - in Greek and Latin).

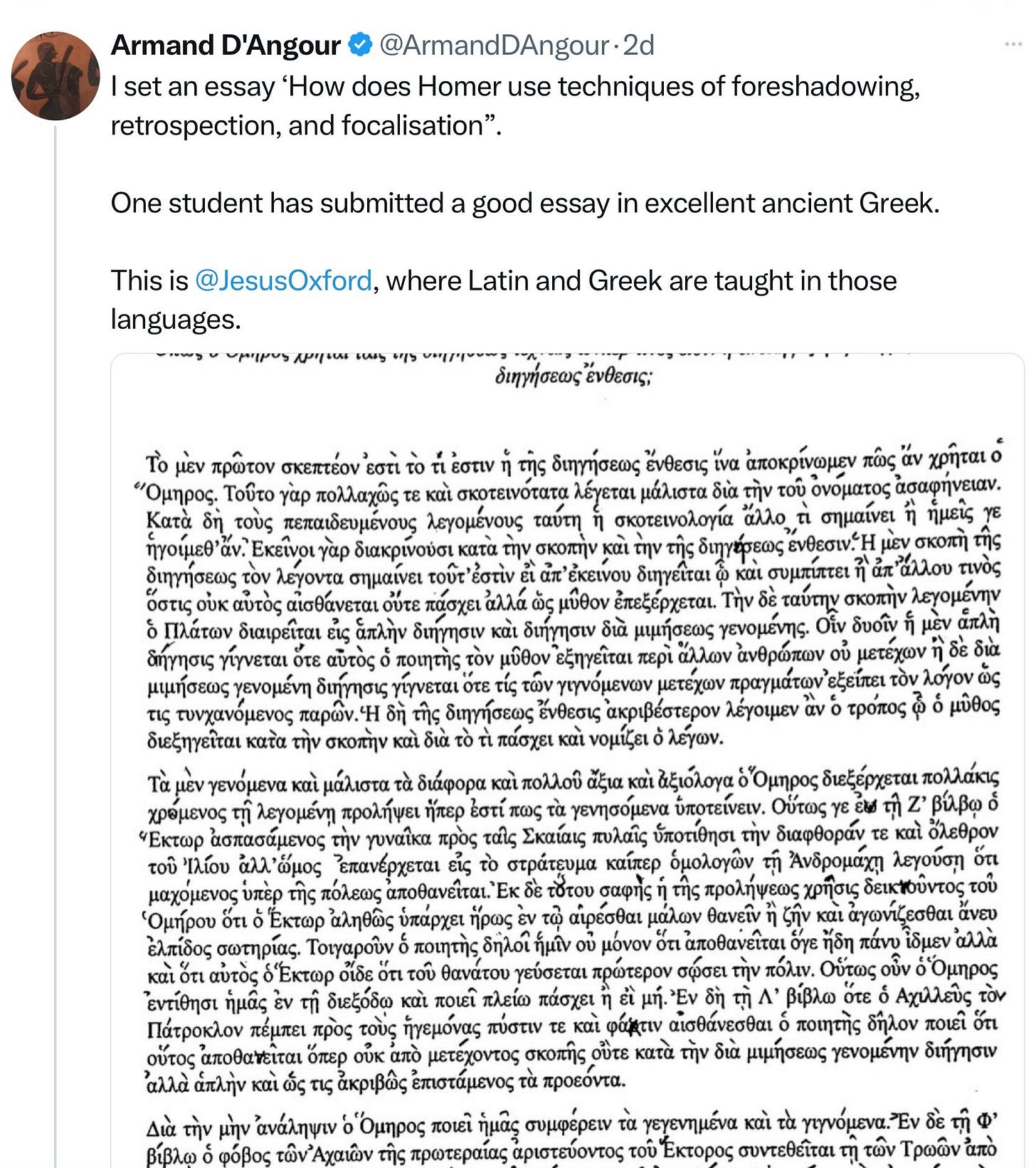

Much of the course still requires, however, that essays on the literature be written in English. So last week I was taken aback when two first-year students decided, as something of an experiment, to submit essays in fluent Greek and Latin.

The first term of the course concentrates on the great epic of Homer, the Iliad, and the essay that was set asked the students to think about literary techniques used in the poem. Among these are foreshadowing, the ominous anticipation of events to come, and retrospection, which is when the poet looks back to events long ago which have led to the present situation. These techniques give a sense that the epic deals with the whole history of the Trojan War, whereas in fact the main action of the poem deals with only a few weeks of the fighting.

How does one say ‘foreshadowing’ and ‘retrospection’ in Greek and Latin? There are existing ancient terms, prolepsis and analepsis, which work fine as translations in either language. But a third technique, ‘focalisation’, is one in which the poet adopts the point of view of, for example, omniscient narrator or a character in the story. One therefore has to ask how such a term might have been thought about in ancient times. Translation is not just about knowing words, but thinking about how things might have been said in their ancient cultural context. Here the Latinist approaches the question of how to think of ‘focalisation’, with my recording of the Latin:

What the students produced (both had done a year’s study of active language, one only online) was extraordinary and commendable. Posted on X as shown above, my brief note about this attracted, rather surprisingly, more than quarter of a million views and a host of admiring comments.

The Greek and Latin of the essays are not error-free, but the writing is fluent and readily understandable; and I asked the students to translate their essays in person into English in a group tutorial to ensure that they really knew what they were saying, and to discuss the content.

If one of the keys to learning to speak a language is being unabashed about using it, the fact that this experiment was even attempted by the students is surely a resounding testimony to the students’ past progress and future prospects (I invoke both analepsis and prolepsis).

Here I read out the first sentences of the Greek essay, using classical pronuncation:

Macte virtute (congratulations!) and εὖγε (well done!) to the students concerned.

Εἴθε κἀγὼ τούτῳ τῷ τρόπῳ ἔμαθον ἑλληνίζειν!

I love this. Bravo to your students!