A Magnificent Drama

Euripides' Orestes in Oxford

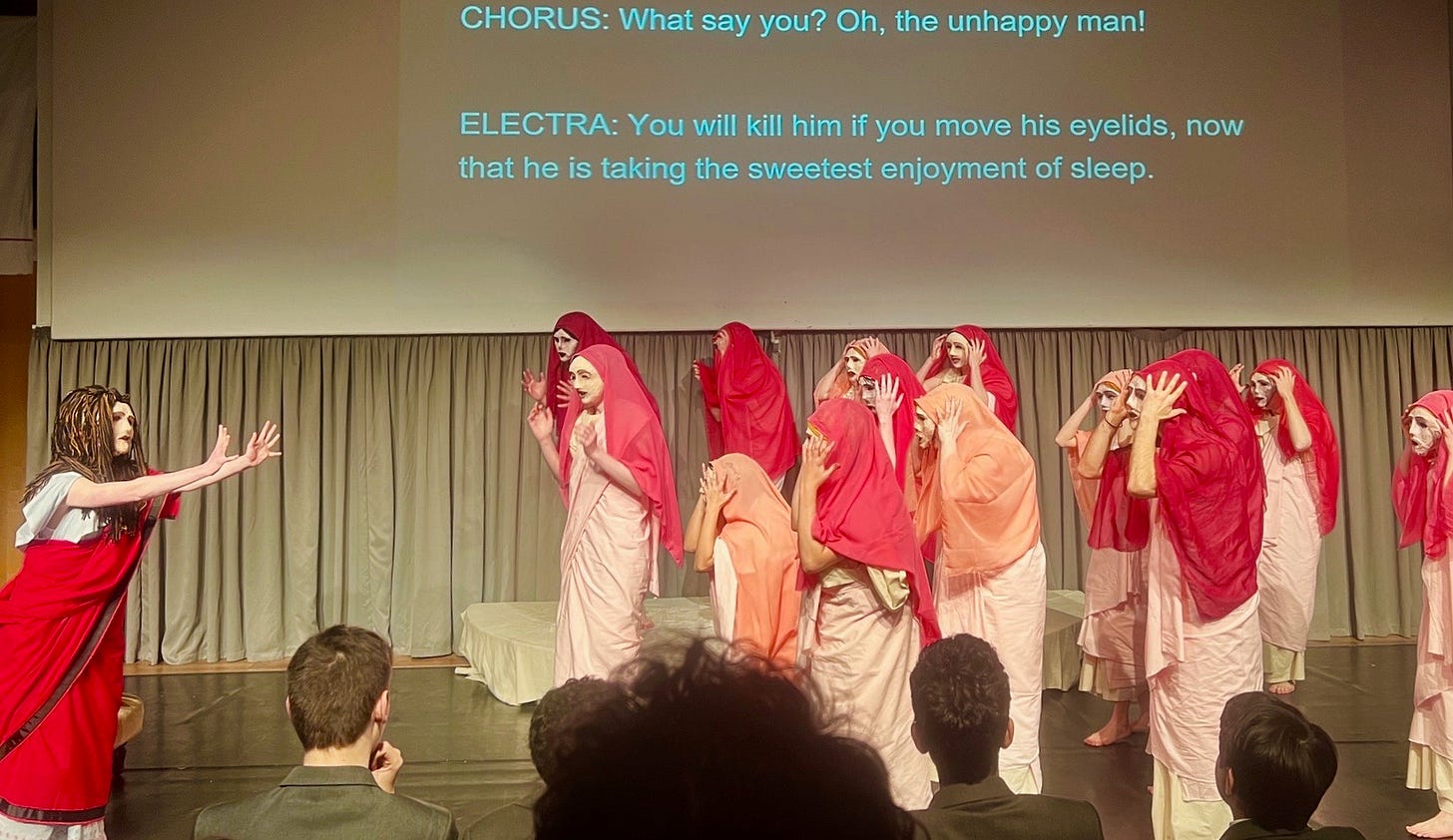

Last week there took place five sold-out performances of a play performed by students in ancient Greek in the theatre of Keble College, Oxford. The play was Orestes by Euripides, originally performed in Athens in 408 BC, and one of the most popular plays in antiquity for centuries thereafter. The staging aimed to be as close to the original in form, language, music, and dance as possible, using every bit of available evidence (e.g. for masks and costuming) and employing the services of the master double-pipe player Callum Armstrong. Surtitles allowed those without Greek to follow the script.

The result was a triumph - brilliant acting, musicianship, and production combined to create what must the finest performance of an ‘authentic’ ancient Greek play since antiquity. The producers Nicholas Romanos and Beth Parker, the actors Althea Sovani (Orestes), Eleanor McIver (Electra), and all those involved in the chorus, acting, and staging, deserve huge congratulation for pulling off a feat that seemed hardly possible.

Orestes is a play of dramatic variety. It begins with the wretched figure of Orestes, who has killed his mother Clytemnestra at the orders of the god Apollo. The faithless Clytemnestra had slain his father Agamemnon after the latter had returned to Argos victorious in the Trojan War. Whatever the justice of the revenge, Orestes was bound to be hounded to madness by the Erinyes, the spirits of vengeance aligned with his mother. At the start of the play, Orestes is snatching a rare moment of sleep between trying to shoot the demons with his bow and arrow, while his sister Electra and the chorus of women of Argos lament (but quietly!) his frenzied state (see photo above).

In due course Orestes faces the anger of the people of Argos in a forensic debate against Tyndareus, who argues that rather than kill Clytemnestra he should have taken her to law. Facing the ultimate punishment, Orestes and his old friend Pylades execute a daring plan to kidnap the general Menelaus’s wife Helen (daughter of Tyndareus) and their daughter Hermione, and hold them to ransom in Menelaus’s palace. Despite making dire threats, Menelaus is in an insoluble predicament: if he storms the palace, his wife and daughter will both die.

Orestes therefore has elements of a lawcourt drama and a hostage crisis - a sure recipe for success. But in addition there’s a scene where a suitably attired Phrygian slave rushes onstage in panic to sing the news of the desperadoes’ actions in broken high-pitched Greek - undoubtedly a scene intended to make the audience laugh (it did).

And the finale? A deus ex machina (literally “god [suspended] from a crane”) whereby Apollo himself appears on the battlements and instructs a peaceful resolution whereby Pylades will marry Electra and Orestes will marry Hermione. Happily ever after!

Not the least exciting feature of Euripides’ Orestes is that a fragment of papyrus survives, dating from around 200 BC, with ancient musical notation (largely alphabetic letters indicating pitch) applied to some of the words of the antistrophe (responding verse) of the first chorus (lines 338-43). Given Euripides’ well known penchant for using avant-garde musico-literary techniques, the fragment is generally considered to represent music composed by the dramatist himself for the production of Orestes in Athens in 408 BC.

In 2016-17 I proposed a reconstruction of the melody of the main areas of the surviving choral passage, together with a speculative restoration of the lost earlier part in the same mode and manner (see Youtube Rediscovering Ancient Greek Music 2017). The melody was to be realised and performed by a choir accompanied by expert auletes Barnaby Brown and Callum Armstrong, playing on auloi (double pipes) reconstructed from ancient instruments found in archaeological contexts.

It was a matter of time before talented classicist-musicians (in this case N. Romanos and Beth Parker) would venture to extend the musical composition along known principles to the rest of the choral portions of the play. They have now done so in a way that allows listeners finally to get a true sense of the way fifteen men or boys (the standard number of an ancient tragic chorus), singing and moving in unison to aulos accompaniment, might have performed that most distinctive and powerful musical feature of ancient drama.

A film was made of the process and the performance, and will be posted as a YouTube video in due course. I predict that it will be a sensation.

I would’ve done anything to see this, so glad a filmed version is coming! When I was a senior in high school, studying drama, part of our course was to - together, as a real independent theatre company - put up a production of whatever play we chose that we could get rights to. I was among those who had an idea, and I presented a (well put together, imo) plan for a production of Oedipus Rex. The one with the winning presentation would be the director. I wanted it to be as close to classical Greek theatre as possible, with the costumes and music and scenery, as we could produce. Ancient Greek theatre is my favourite style, and I spent a lot of time thinking about this production. Sadly, my class didn’t share my ancient sentiments, and chose Clueless (after the movie) instead… I wasn’t surprised (I knew my classmates didn’t share my enthusiasm for Greek theatre) though a little sad. I still have that PowerPoint presentation; my dream would be to one day realise it. Perhaps if I ever get rich, or somehow a high enough rank in local theatre groups, I’ll make it come true with my own company.

I am even more in awe! What an achievement! Scholarly virtuosity in action in your melody reconstruction.

To what extent are you responsible for the performance?

Respectfully yours,

An old teacher of mathematics