Many years ago I came across the Latin phrase used by the Latin poet Horace (1st cent BC), 𝑎𝑑 𝑢𝑛𝑔𝑢𝑒𝑚 𝑓𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑢𝑠 ℎ𝑜𝑚𝑜 - ‘a gentleman to his fingertips’. Since we have a similar metaphor in English, it caused no difficulty, though ad unguem literally means ‘to the nail’ (i.e. fingernail or toenail). The sense was clearly that such a person was admirable through and through, to the furthest extremity of the body.

Later, however, I came across the phrase ad unguem used on its own by Horace, when advising that a poet should refine his verses ‘to a T’ (as we might say). Since a poem doesn’t have fingernails, I wondered what the true source of the image might be. The equivalent phrase in Greek (eis onycha) appears in a passage of a book by the great 5th-century Greek sculptor Polykleitos of Argos: “The sculptor’s task is hardest when the clay comes to the nail”.

This puts a new complexion on the meaning of the phrase, which Latin took from Greek: it was about the fine details of a work of art. The process of bronze casting (known as cire perdue, ‘lost wax’) required creating a mold and covering it with clay. Fine details such as fingernails and toenails were carved into the mold before the whole thing was covered in wax. It was then placed in a pit and molten bronze poured over it. This would melt away the wax and take the imprint of whatever had been carved into the clay. The bronze cast would then be finished and polished.

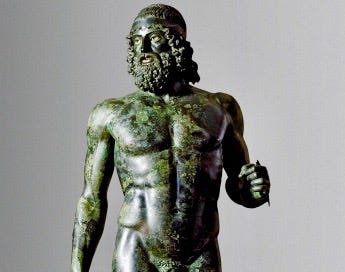

The ‘hardest task’ for the sculptor would have been covering the fine extremities of the mold with clay without damaging or breaking them. ‘To the nail’ didn’t refer to the living nails of the poet, but to the nails on a bronze statue - such as those found on the hands and feet of the magnificent Riace bronze shown above. (‘You nailed it’ punned a colleague when I published in 1999 my article Ad Unguem, which I’m happy to share with anyone who requests it).

A similar Latin phrase a tenero ungui (‘from the tender nail’) does refer to a person’s own finger/toenail as representing the furthest corners of their frame. The Greek version of that phrase (ex onychôn) is used in this AD 3rd/4th-century epigram by Rufinus, ‘The Kiss’:

Europa’s kiss is sweet, though to my mouth

she barely comes, and only skims my lips;

But when she settles on my mouth, she wrests

the very soul up from my fingertips!

Εὐρώπης τὸ φίλημα, καὶ ἢν ἄχρι χείλεος ἔλθῃ,

ἡδύ γε, κἂν ψαύσῃ μοῦνον ἄχρι στόματος·

ψαύει δ᾽ οὐκ ἄκροις τοῖς χείλεσιν, ἀλλ᾽ ἐπιβᾶσα

τὸ στόμα τὴν ψυχὴν ἐξ ὀνύχων ἀνάγει.

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Interesting difference in emphasis - the quality does not reside in a man's inherent being but in what others admire in him. 'Skin-deep,' if you like, but then who ever said "yes it's a hideous statue, but the spleen within is really excellent"?